Care: Physical health

Care: Physical health

Respect the species, know the individual

We are immediately responsible for doing the best we can in the care we give each cat when it comes into the homing centre.

One of the important principles of Cat Friendly Homing is that cats do not leave a homing centre less physically or mentally healthy than when they arrived.

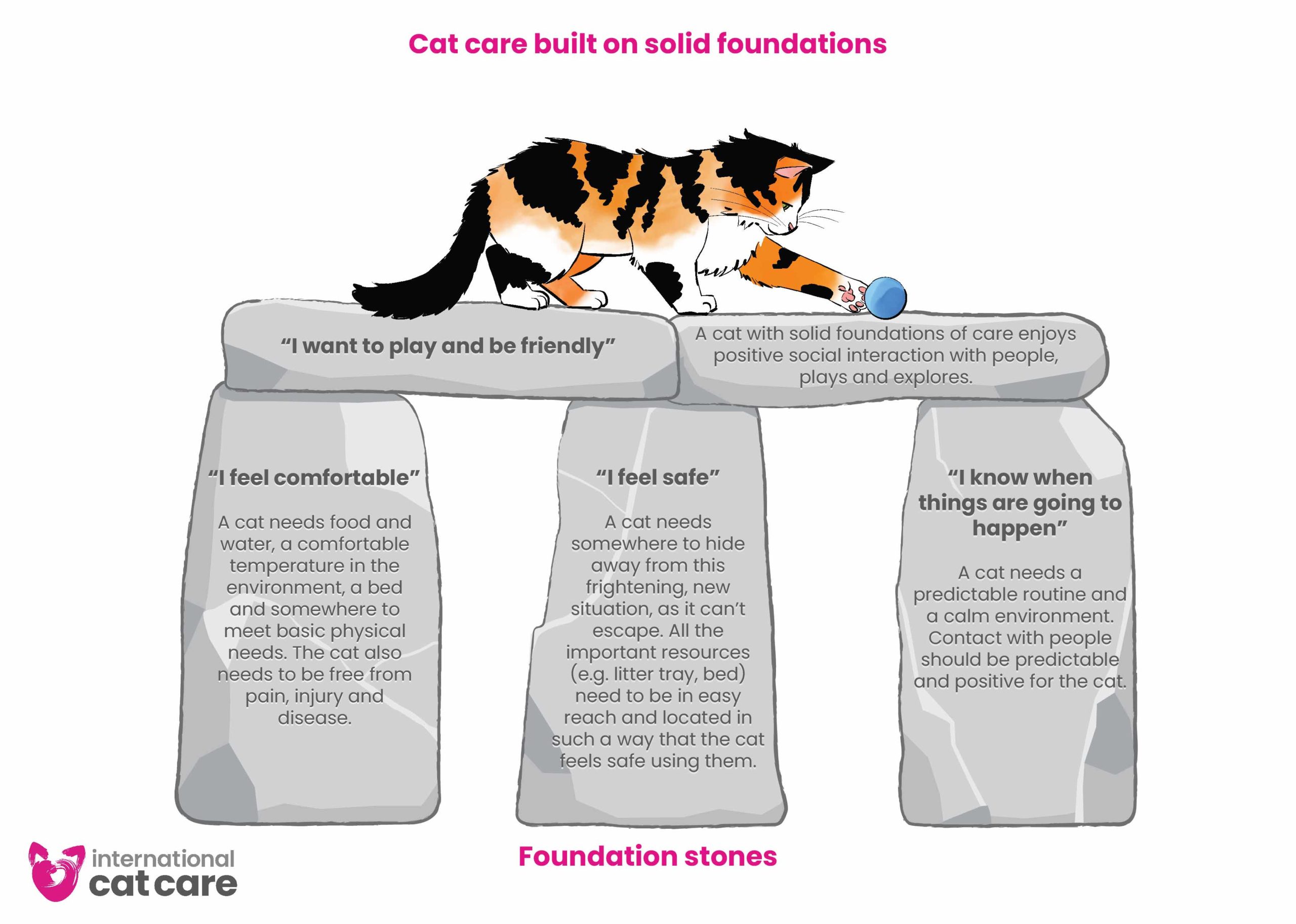

Certain aspects of care should always be prioritised, for example, it isn’t going to help the cat to put toys in its pen/cage if it doesn’t have food, water, somewhere to sleep and somewhere to go to the toilet. It isn’t going to help the cat to give it affection if it doesn’t feel safe. Equally, resolving pain and suffering should be a primary concern before you consider how much interaction the cat may want with you.

It may help to view these elements of care as the foundation stones, fulfilling the cat’s basic physical needs, such as eating and drinking, treating any pain or discomfort and ensuring it feels safe. The foundation stones are the basics upon which you build everything else, such as interaction and play.

Keep cats as physically healthy as possible

Cats in a homing centre pose a challenge where keeping them physically healthy is concerned because:

- The centre brings together large numbers of cats of unknown vaccination or health status

- The place where cats are housed may not have been designed for ease of cleaning or preventing the spread of disease

- Many cats move in and out

- Overcrowding is common

- Veterinary care may not be readily available

- It can be very difficult to recognise when cats are feeling unwell or are in pain and staff may not recognise subtle signs

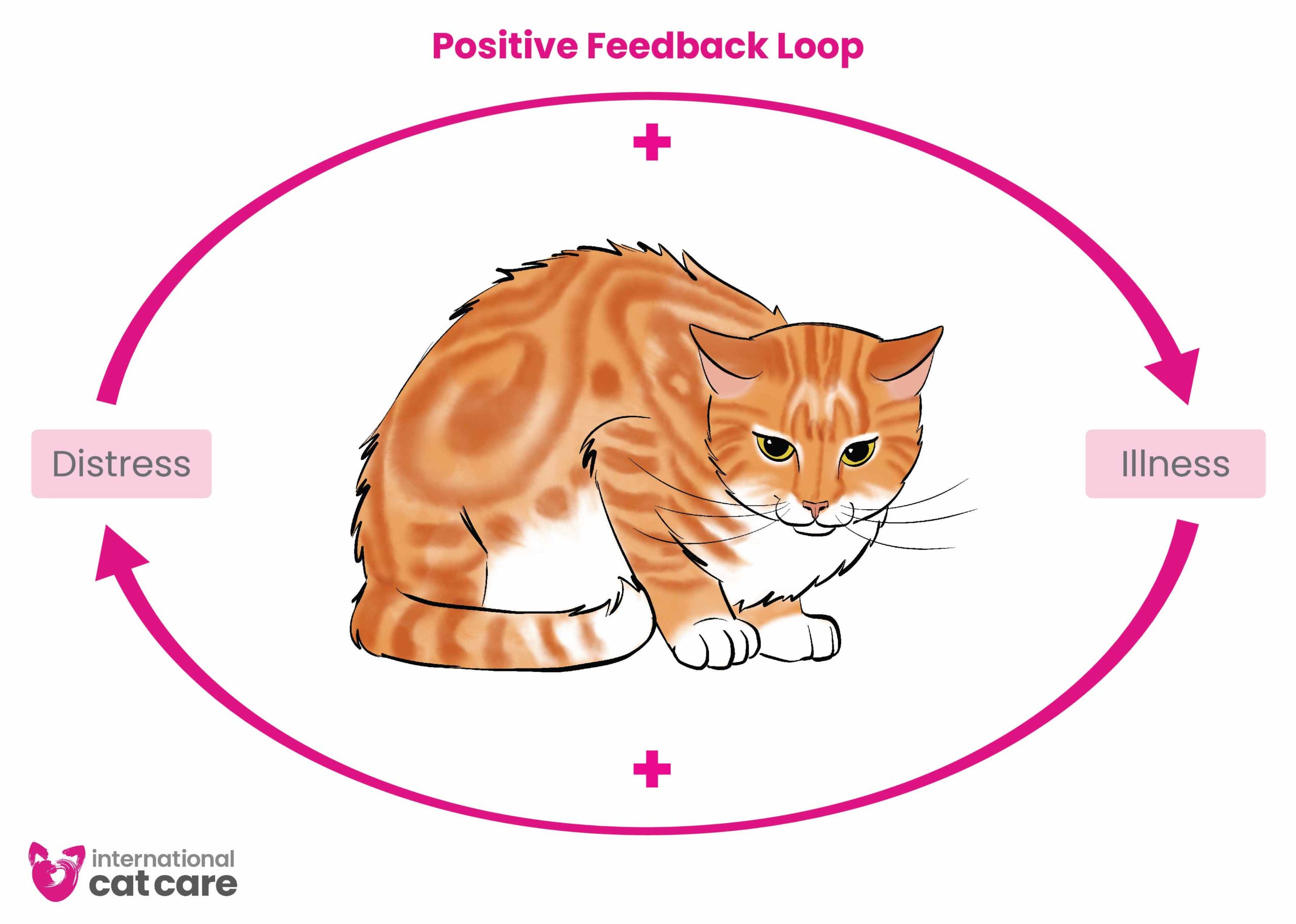

For cats, distress can exacerbate disease and increase the risk of spread. A homing centre can cause cats distress. So health and emotional distress are closely linked and can both promote each other

Distress leads to illness and vice versa

Steps in keeping cats physical healthy

- Assessment of cats’ health

- Housing and management of cats to prevent the spread of disease

- Good nutrition

- Preventive health care

- Record health and continue to monitor

| Working with your veterinary partners

Good health cannot be achieved or maintained within a homing centre without good veterinary advice and care for the cat. The veterinary team you work with, whether it is private practice or as part of your organisation, are vital to the health and welfare needs of the animals in your care, neutering surgery and humane euthanasia when necessary. When veterinarians work with organisations that care for unowned cats they adopt what is called a ‘shelter medicine’ approach. This means that they always have to consider that the treatment of one individual may affect the potential health and treatment options of all the cats in the centre. This is especially true when thinking about diseases which spread easily between cats and covers both prevention and treatment. This results in a pragmatic approach to decision-making. They also have to take into consideration the different ethical standpoints of the organisations they are working with and the resources available. A good relationship with your veterinary team is vital and the relationship can be enhanced by:

|

Assessment of cats’ health

Most homing centres do not have the luxury of in-house veterinary care. Therefore, the staff need to be able to look at a cat to ascertain whether it needs urgent veterinary care or can wait for a more routine visit or transport to the veterinarian at a later time.

A lot of information can be gained about a cat with an initial and basic visual examination and observation before any attempt is made to handle it. It is advisable to leave a cat in a quiet area for about 15 minutes after being transported to allow it to settle.

Points to consider during an initial visual examination:

- What is the cat’s coat condition?

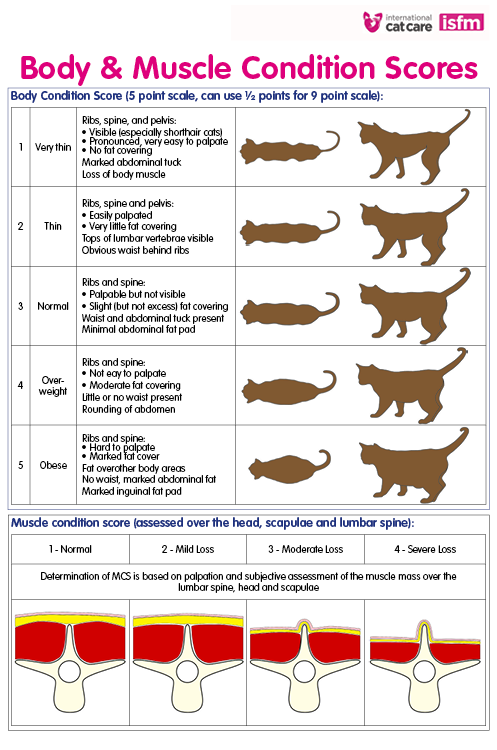

- Is the cat thin or overweight? (see body condition score)

- Are there signs of diarrhoea or soreness under the tail

- Is there a discharge from the cat’s eyes, nose or mouth?

- Are there any obvious injuries or abnormalities?

- Does the cat’s breathing appear normal or is it rapid, noisy or laboured?

- Does the cat’s behaviour and body language suggest it is relaxed (eg, rubbing against the bars of the cage), aroused (eg, on edge, visually scanning its surroundings) or distressed (eg, behaving aggressively, actively trying to hide)?

Cat Care for Life Body & Muscle Condition Score Chart

Some issues that arise from an initial visual examination may require immediate veterinary input, for example, collapse or laboured or open-mouth breathing which is not simply like panting in dogs but is caused by serious respiratory problems. All observations should be noted on the cat’s records for future reference.

The table below outlines some basic signs of good health and poor health. Veterinary help should be sought if there are signs of illness. If in any doubt about the cat’s health, isolate the cat and seek veterinary advice as soon as possible.

| Signs of good health | Signs of poor health |

| Bright and alert | Lethargic |

| Clear, bright eyes | Discharge from eyes, sore, redness, swollen |

| Clean ears | Dark brown or black waxy discharge from ears |

| Clean nose and face | Discharge from nose, snuffling or sneezing |

| Glossy, parasite-free coat | Coat dirty or ‘staring’ (hairs of the coat, instead of lying flat and being smooth and shiny, are standing up, separated and dull). Visible signs of itchiness or parasites |

| Good appetite and drinking normally | Poor appetite or no appetite; excessive thirst, or drinking a lot |

| No vomiting | Vomiting |

| Neither too thin nor too fat with no evidence of muscle wastage (e.g. prominent spine) | Weight loss – the cat is thin |

| No obvious stiffness in joints when the cat moves | Reluctance to move or jump up on higher objects. Stiff gait (way of walking) |

| The inside of the mouth and eyes are pink | Membranes may be pale indicating anaemia or have a yellow hue, indicating liver problems |

| No bad breath, bad teeth or mouth ulcers | Bad breath, looking interested in food but not eating, which may indicate mouth pain |

| Regular urination or defecation | An increase or decrease in the frequency of urination or defecation – constipation or straining |

| Urine is passed with no apparent discomfort | Straining or apparent pain when urinating or blood in the urine |

| Faeces are firm and brown | Diarrhoea, faeces which are fatty or greasy with an unusual smell, fresh blood faeces, black faeces, mucous or slime in faeces |

| No presence of roundworm, tapeworm or blood in the faeces | Presence of parasites or blood in faeces |

| Normal posture | Hunched posture |

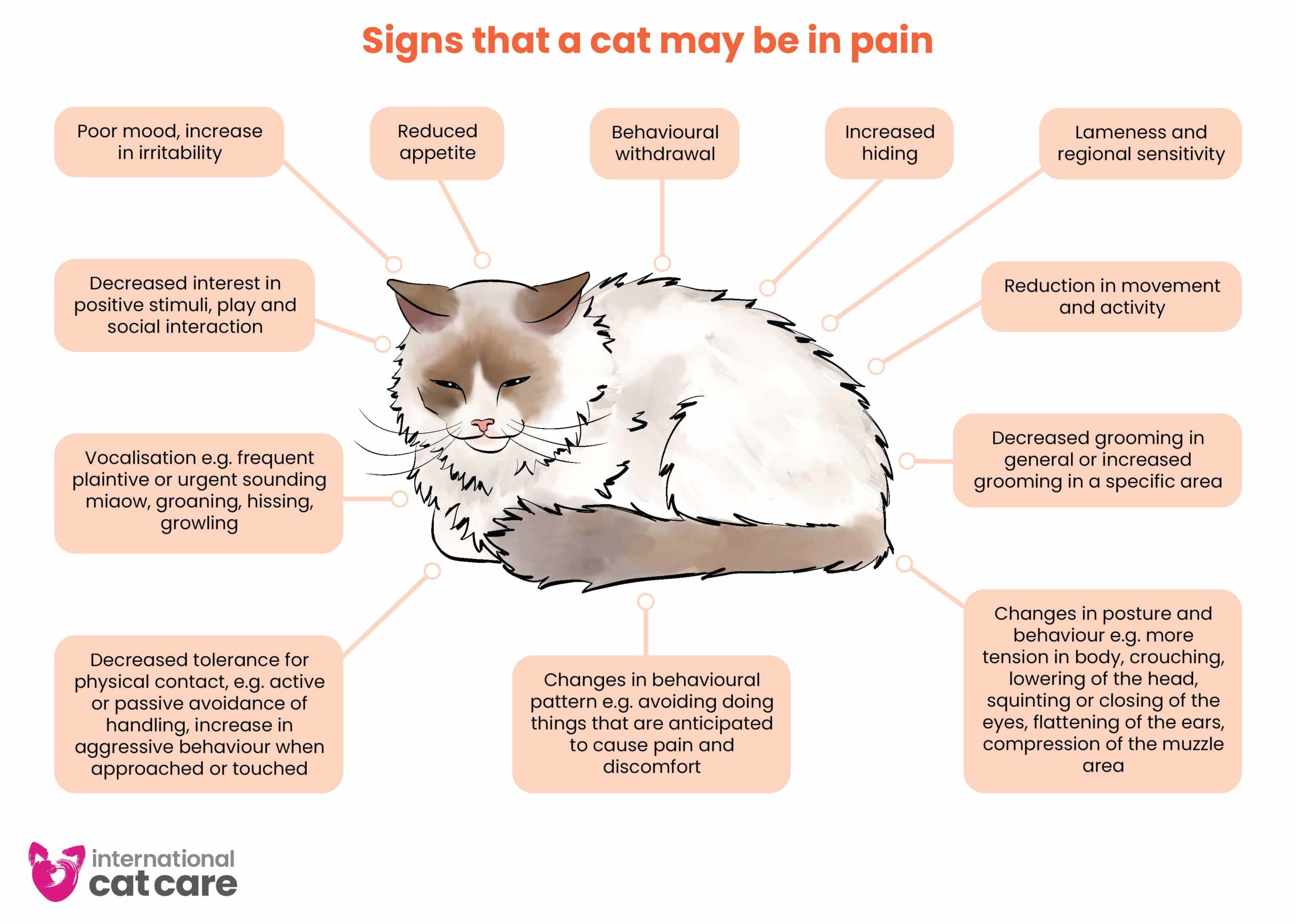

| No signs of pain | Signs of pain – see table |

These cats look healthy

This cat looks in poor health

The cat in the front looks healthy but the cat behind it is in poor health, with bad discharge from both eyes causing the loss of fur

| Recognising pain

The cat’s ancestry has a great influence over its behaviour. Cats have evolved to be self-reliant and therefore they are solely responsible for their own survival. It is important for them to hide signs of vulnerability, so they are notoriously difficult to read when it comes to identifying signs of pain. It is, however, essential for you to be able to assess the basic physical health of the cats in your care and spot if veterinary intervention is necessary as early as possible. The following diagram shows the many and varied signs that a cat may be in pain.  Signs to look out for that a cat may be in pain |

Housing and management of cats to prevent spread of disease

Effective disease control matters to all homing centres because they are ‘high risk’ places. Having an outbreak of infectious disease, such as cat flu or enteritis, in a homing centre can mean that many cats suffer and the centre may have to be closed to new cat admissions until the problem has been solved. A huge risk can be that staff and volunteers may not understand the importance of disease controls, even as simple as washing hands between touching cats (true also of foster situations, where infection control may be non-existent). Some cats, although appearing healthy, may be carrying or incubating diseases that are not immediately obvious.

The type of infectious disease and how common it is can vary from country to country and even between regions or areas, so it is essential to be aware of those diseases that are commonly seen in your area.

- Cat ‘flu (a group of respiratory diseases including the feline herpesvirus and the feline calicivirus)*

- Bordetella bronchiseptica

- Feline chlamydia

- Feline parvovirus (also known as feline infectious enteritis or feline panleukopenia)

- Feline leukaemia virus (FeIV)*

- Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV)*

- Feline coronavirus and feline infectious peritonitis (FIP/FCoV)*

- Rabies – in countries where this is present

- Ringworm

- Infectious causes of diarrhoea

- Internal and external parasites

| Useful information:

Here are links to policy statements FIV, FelV and FIP/FCoV, created by The Cat Group, a collection of professional organisations in the UK dedicated to feline welfare through the development and promotion of policies and recommendations on the care and keeping of all cats. http://www.thecatgroup.org.uk/policy_statements/fiv.html http://www.thecatgroup.org.uk/policy_statements/felv.html http://www.thecatgroup.org.uk/policy_statements/fip.html AAFP Feline Retrovirus Testing and Management Guidelines, JFMS 2020

|

Diseases can be spread by:

- Cats sneezing on each other

- Cats grooming each other

- Cats sharing litter trays

- Cats fighting

- People carrying diseases from cat to cat on their hands, equipment or clothing

Whatever protocols are put in place to prevent the spread of disease, it is essential these are carefully thought through and all members of staff understand the benefits and how to follow them.

Ways to reduce the spread of infection:

- Design/structure of the cat housing

- Management of cats

- Cleaning and disinfection of the cat housing

Design/structure of the cat housing

Ideally, cats should be kept in a facility/cattery designed for the purpose.

- Individual housing is best to prevent cats from coming into contact with each other

- If group-housed, it is recommended that the maximum number of cats does not exceed six per group but that the decision of how many takes into consideration the amount of physical space and number of resources within the available space

- Barriers should be in place between cat units to prevent the spread of infection by sneezing

- Premises where cats are housed should be well ventilated and temperature regulated (not too hot or too cold)

- Good drainage is essential to ensure dry flooring – some micro-organisms that cause disease multiply in damp conditions

- Surfaces which the cat has access to should be smooth and kept in good condition so that they wipe clean easily

- An isolation facility should be used in the event of a cat becoming unwell to remove it from the main cat area where it can be a source of infection for other cats

An isolation facility removes a sick cat from the main cat area to prevent the spread of disease

- A quarantine facility should be used for new arrivals of unknown disease and vaccination status, depending on the cattery design and management. Quarantine can extend the period that a cat is confined and requires a move within the homing centre after quarantine, both of which can be stressful. So however it is done, it should be done well taking the following into account:

- Well designed and well managed single cat units where cats cannot sneeze on or touch each other and where other disease control measures are put in place are much more secure for disease control and isolation may not be necessary

- Cats kept in units where they can touch each other, either directly or through wire or mesh walls, are at a much higher risk of transferring disease from one to another via sneezing or touching and an isolation period would be useful

- Housing a number of cats from different origins in multi-cat units where cats share litter trays brings a high risk of spread of disease, and a period of quarantine is probably important. However, the quarantine facility must ensure all the cats housed there are isolated from each other and strict hygiene protocols adhered to, otherwise, cats actually catch disease in quarantine facilities!

This homing centre in Portugal does not have the finances to afford single cat housing but they provide large pens with multiple levels and essential resources for a total of 6 cats (their goal is to provide single cat housing in the future)

Management of cats to minimise spread of disease

- Ideally cats from different sources should not be allowed to have direct contact with each other, ie cats should not use communal runs or exercise areas (in some homing situations this is unavoidable but must be recognised as a disease risk and cause of distress)

- Illness must be identified promptly and steps taken to stop disease spread and to get treatment started

- Testing for infectious disease can be helpful to prevent spread or recurrence as well as identifying the correct treatment

- Adherence to a strict cleaning policy (including standard operating procedures that all staff follow) is vital to successful management of infectious diseases

- Accurate record keeping of a cat’s health prior to arrival (if known) and daily during the cat’s stay can help to identify problems

- Using vaccination to prevent disease is a useful tool

- Minimising movement of people through the cattery (carrying infection from one cat to another) is important

- Washing hands between touching cats or cleaning bowls or litter trays is vital

- Limiting the time the cats stay in the centre reduces the risk of catching disease

- Using quarantine and isolation according to the design of the centre and the health of the cats can help to prevent spread of disease

Cleaning and disinfection of cat cages

The importance of good cleaning routines should never be underestimated. It not only presents a positive image for your homing centre but it reduces the risk of disease transmission and provides a clean and healthy environment for the cats in your care. In order to have the right cleaning regime for your environment, you need to know the infectious diseases that are prevalent in your area and therefore those you are most likely to encounter.

| Do the best you can

You may be reading some of the content on this page and thinking ‘I can’t do that’ or ‘I wish it was that simple!’ We know that life is complicated and when you are dealing with cats (and people) nothing is black and white. Following Cat Friendly principles is all about doing the very best you can under difficult circumstances. So, if you read something and think ‘impossible!’ then maybe consider what you could do instead that would have a positive impact. We know we cannot achieve perfection as it isn’t a perfect world. Be pragmatic and be satisfied with ‘good enough’ when the ideal seems impossible. |

A good cleaning protocol includes:

- The removal of all soiled bedding and litter

- The removal of dirt, urine, faeces, vomit etc. from all surfaces

- Washing with hot water and detergent, leaving a visibly clean surface

- Disinfection, using a chemical on surfaces, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, once the area has been prepared appropriately, ie debris/dirt has been removed. Products vary but it is important to follow instructions regarding recommended surface contact time before the chemical is rinsed off

- Using disinfectants that are not toxic to cats

- Bedding, towels and staff/volunteer uniforms should be separated and washed in hot water and detergent

- Cleaning water and food bowls with hot water (minimum 77ºC)

- Using mops and high-pressure hoses should be avoided as they can harbour and spread disease respectively

- Hygiene precautions should be taken between handling cats, eg hand washing

- Cages should be completely cleaned and disinfected between being used by different cats

- Frequent cleaning of litter trays is important, especially where cats are group-housed

However, there has to be a balance between the perceived risk of infection and the needs of the cat as a species to maintain a familiar scent around them to help them feel safe. Often excessive cleaning regimes destroy any scent marking or familiar odour and disrupt the cat as it is removed during the process. In the absence of an actual, identified infection risk, pens/cages should ideally be ‘spot cleaned’ which means allowing the cat to remain there while its beds are tidied, litter tray scooped/cleaned and any remaining food and water are replaced with fresh.

Disease control in foster care

|

Zoonotic disease

- A zoonotic disease is one that can be transmitted from animals to humans, eg rabies, so it is important to have some knowledge of these and how to minimise risk see https://iacuc.wsu.edu/zoonoses-associated-with-cats/

For more information, see International Cat Care’s cat health advice pages

Good nutrition

Cats are referred to as ‘obligate carnivores’ which means they need protein from a meat source in order to survive. A good diet is important to maintain the health of the cats in your care, see https://icatcare.org/advice/feeding-your-cat-or-kitten/

There are some specific things to consider for cats in homing centres:

- Dry food is more hygienic to feed than tinned or sachet food in hot climates/weather

- Try to stick to one brand of food if you can to avoid any digestive problems that can occur with constantly changing food. If multiple brands are used then consider mixing them to provide a constant diet

- Keep some palatable wet food available for using in small quantities for mixing with medication, when needed

- Do not be tempted to offer large quantities of food as cats can become overweight in confinement

- Feed to maintain body weight (if within a healthy range), bearing in mind that cats are not using much energy in a pen/cage

- If you are keeping cats in multiple housing then ensure there are sufficient separate feeding stations to enable all cats to eat separately from each other

Preventive health care

Parasite control, vaccination and other preventive healthcare procedures will ideally be carried out according to the cat’s general health and on veterinary instruction. However, having a good relationship with your veterinarian may mean that they can instruct you when it is appropriate for you to give basic treatment, such as parasite control, in their absence.

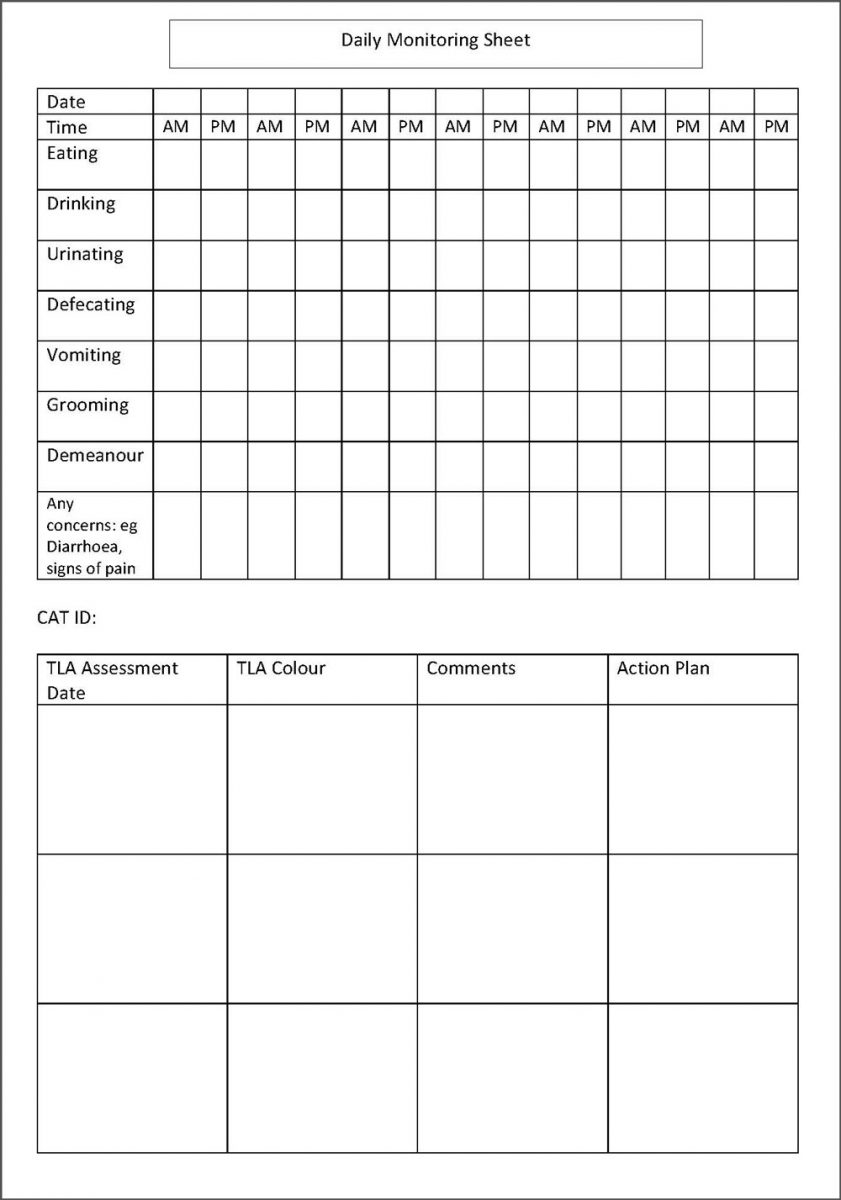

Record health and continue to monitor

Keeping a record of a cat’s day to day life during its stay in a homing centre is essential to ensure quick intervention if the cat is unwell and to know as much as possible about it to find the outcome that suits the cat’s needs. This paper record of the cat’s food and water intake together with its toilet habits and how it is behaving should be noted on a sheet attached to the cat’s pen/cage so that anyone caring for that cat can instantly get an idea of how the cat is coping if it is well and what action plan has been put in place to ensure it is as physically and mentally healthy as possible. It is important that everyone maintains the same style of objective comments such as ‘the cat remained hidden in its bed’ rather than using interpretive or subjective wording, such as ‘the cat is shy’, ‘the cat is annoyed with me’ or ‘the cat is so sweet’. This helps everyone to get a sense of how the cat is coping without trying to guess what the person writing the comment is actually seeing. Complimentary sentiments about the cat may be viewed by us as a positive thing but, in reality, they do not provide any useful information about how to care for that cat.

Here is an example of the kind of minimum information you can record for each cat.

If the cat is receiving any treatment or under the care of a veterinarian you will also need to have a form that has clear instructions of what medication the cat is receiving and when together with information about the cat’s condition and when any check-up is due.

Make sure cats and kittens are neutered

Population management is an essential part of your work so every cat or kitten that comes into your care should be neutered (females spayed and males castrated) before they leave to go to their new home. Veterinary practices are now rethinking the more traditional timing of 6 months of age and neutering male and female kittens from pet homes at 4 months of age and feral and unowned kittens from 8 weeks.

| Neutering information

iCatCare information on neutering The Cat Group policy statement on neutering The Cat Group is a collection of professional organisations in the UK dedicated to feline welfare through the development and promotion of policies and recommendations on the care and keeping of all cats. International Cat Care is a member organisation of the Cat Population Control Group promoting neutering of pet cats in the UK. This is the summary of evidence for neutering at four months The Kitten Neutering Database lists veterinary practices in the UK that routinely neuter at 4 months. |